The Shawshank Redemption: A Tale of Silent Rebellions and Transformational Hope:

Released in 1994, The Shawshank Redemption has become a cinematic landmark, celebrated for its exploration of friendship, hope, and the human spirit. What distinguishes the film is not merely the narrative of a man unjustly imprisoned but the subtle revolutions that unfold within the confines of Shawshank State Penitentiary. Beneath the surface of the conventional prison drama lies a deeper, almost spiritual meditation on the essence of freedom, personal redemption, and the quiet defiance that happens in seemingly small, individual choices.

Cast

Tim Robbins

Andy Dufresne

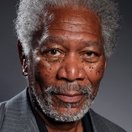

Morgan Freeman

Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding

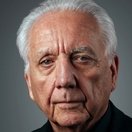

Bob Gunton

Warden Samuel Norton

William Sadler

Heywood

Clancy Brown

Captain Byron T. Hadley

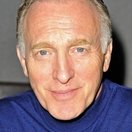

Gil Bellows

Tommy

Mark Rolston

Bogs Diamond

James Whitmore

Brooks Hatlen

Silent Rebellions in a World of Control

In Shawshank, the obvious markers of control are physical: high walls, bars, and armed guards. But the truer, more pervasive control is psychological. It is the way prison breaks down men, making them believe they belong in captivity. Brooks Hatlen’s tragic story demonstrates this. After spending fifty years behind bars, Brooks cannot cope with life outside. He’s become “institutionalized“—a state where the outside world feels more confining than his cell. The notion of a free man trapped by his mind reflects one of the film’s central themes: true imprisonment is internal.

Andy Dufresne’s quiet defiance lies not in grand gestures but in the minute acts of autonomy that challenge the oppressive environment. His decision to carve chess pieces from stones, to transform the prison library, or even to lock himself in the warden’s office and broadcast The Marriage of Figaro over the loudspeakers, are moments of silent rebellion. These acts aren’t designed to provoke escape in the literal sense but to remind those around him that the human spirit can never be fully confined.

In the world of Shawshank, escape is not just about tunneling through walls but about preserving the essence of self, in the face of systematic degradation.

The Architecture of Hope

Hope, as Red explains early in the film, can be dangerous. For those trapped in Shawshank, hope is a double-edged sword. It can keep men alive, but it can also drive them mad. Red himself, despite his wisdom and humor, has buried his hope deep, convinced that to survive prison, one must abandon such dreams. He offers a pragmatic view—hope leads to disappointment.

But Andy’s hope is not a naive yearning for a better future; it is a disciplined practice. It is present in his routine of slowly chiseling away at the walls of his cell, a process that takes decades. This meticulous patience is a form of faith, not in some grand deus ex machina to free him, but in the idea that freedom is something one must continuously work toward.

Andy doesn’t just preach hope; he shows it. When he asks Red to help him with his dream of escaping to Zihuantanejo, he plants a seed of hope in Red. By the time Red is released, it has grown into something tangible—a belief that there is something better beyond the prison walls. The idea of hope, therefore, shifts from something dangerous and out of reach to a kind of freedom that can be cultivated even within the confines of Shawshank.

Redemption is a Personal Journey

What does it mean to be redeemed? For Andy, his redemption is rooted in reclaiming his sense of self, in finding meaning in a situation designed to strip it away. He transforms Shawshank from a place of despair to one where books, music, and learning flourish. However, Andy’s journey of redemption is less about his innocence or escape and more about the internal process of becoming whole in a fractured world.

Red’s journey, on the other hand, is far more internal. Unlike Andy, Red is guilty of the crime that put him in Shawshank, but his redemption does not come from forgiveness. It comes from realizing his worth and acknowledging the future he once dismissed. In his final parole hearing, Red finally stops trying to perform for the system. In accepting his past and embracing his humanity, he achieves a kind of personal redemption that transcends the walls of the prison.

The Prison as a Mirror of Society

What is often overlooked in discussions of The Shawshank Redemption is the way the prison functions as a microcosm of society. The rigid hierarchy, the abuse of power, and the corruption of the warden mirror the larger systemic flaws in the world outside. Warden Norton’s obsession with religion as a tool for control reveals how systems—whether they be prisons, governments, or institutions—often function by manipulating hope and faith for their ends.

At Shawshank, morality is often inverted. Those who are supposed to uphold justice (the wardens, the guards) are corrupt and self-serving, while criminals like Andy and Red exhibit traits of loyalty, dignity, and kindness. The juxtaposition forces the viewer to reconsider what justice, punishment, and morality truly mean outside the neat boxes society tends to place them in.

Conclusion: A Testament to the Quiet Revolution

The Shawshank Redemption resonates not because of its grand, dramatic moments but because of its focus on the slow, internal revolutions of its characters. It offers a meditation on how we, like Andy, can slowly chip away at our walls—those internal barriers that confine us. Redemption is not merely about atoning for past sins but about reclaiming the freedom to define oneself, even in the most oppressive conditions.

In this sense, The Shawshank Redemption remains a universal story, not of jailbreaks or legal battles, but of the quiet, often unseen battles that define the human spirit’s struggle for meaning and hope in a world that usually seeks to crush both. It’s a film that asks us: Can we, like Andy, choose hope in the face of despair? Can we carve out freedom in the small, deliberate acts of personal rebellion? And ultimately, can we redeem ourselves, not through escape, but through transformation?

That is the true power of The Shawshank Redemption—the idea that redemption lies not in a dramatic finale but in the incremental, personal choices that shape who we become.